Vietnamese Tea: Origin, Geography, Cultivars, Current Affairs

Vietnam is a country of contrasts and its tea industry is no exception to this rule. Location and geography allow tea to grown in the sub-tropical north as well as the tropical south. Vietnam forms part of the cradle of tea, yet, has a relatively young tea industry. It continues to pursue rapid growth in commodity products, but the shoots of specialty tea are starting to break through. What can you expect to find in your Vietnamese cup of tea?

Land and History

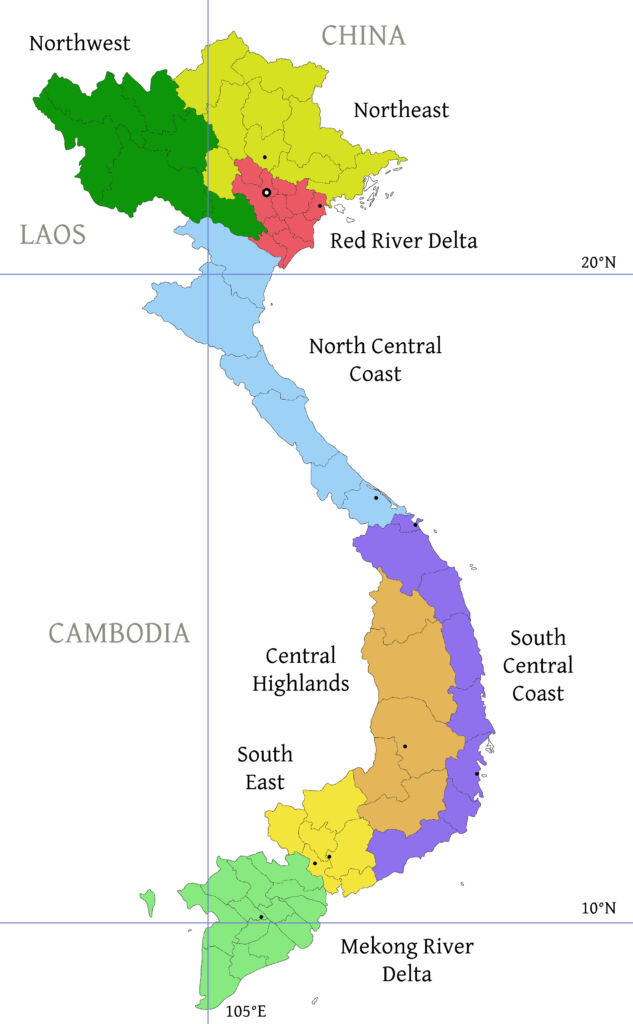

Map of Vietnam with regions highlighted

For most of its history, tea in Vietnam was a garden crop while the tea culture that developed among Vietnamese nobility was mainly influenced by China and Chinese teas. The development of an organised tea industry towards the end of the nineteenth century was inspired by French colonialists who saw an economic opportunity to satisfy domestic demand as well as that of her North African colonies. An initial period of impressive growth was subsequently brought to a halt by the decades of conflict that started with World War II. But, since the opening up of the Vietnamese economy in the 1980’s, the industry has developed steadily and has seen the country become established as a top tea producer and exporter, sixth in the world.

Vietnam’s unique geography creates an interesting difference between tropical south and sub-tropical north that affects climate, agriculture, and attitudes. The country stretches 1,650 km (1,025 miles) from north to south while distances from east to west range from 600 km (372 miles) at its widest in the far north to a mere 50 km (31 miles) at the narrowest. In area, Vietnam is a little smaller than Japan, Germany and the US state of Montana but a little larger than Norway, Italy and the state of New Mexico.

More tellingly, the whole of Vietnam would fit comfortably into the area occupied by Yunnan Province. As the majority of Vietnam tea is produced in a relatively small area, comprising the most northerly provinces, and as it is a relatively modern industry, there is nothing approaching the range of variety and styles of teas that are found in China. Even so, differences in soil, terrain, elevation and processing practices still provide plenty of choice despite the absence of dramatic regional differences.

Tea is grown in over a half of Vietnam’s provinces but most productively in Lam Dong (in the Central Highlands), Thai Nguyen, Phu Tho, Tuyen Quang, Ha Giang (all in the Northeast), and Yen Bai (in the Northwest), provinces.

A Fledgling Specialty Tea Market

In Vietnam, as in other tea producing countries, government and trade associations focus on volume, costs, productivity, and yields. It is a fact of life (certainly in Vietnam) that the majority of tea is commodity, mass produced and sold on price rather than origin.

The specialty market is new and growing but remains niche and small. Evidence of increased interest and curiosity in quality teas from ‘newer’ origins, such as Vietnam, exists and producers and vendors are starting to take notice of this market.

For anyone searching for specialty Vietnamese tea my recommendation would be three avenues of exploration: traditional green tea from Tan Cuong; the emerging oolong tea market; and the variety of teas produced from wild tea trees.

Tan Cuong

Northeast Vietnam tea growing regions

The best-known tea of Vietnam, green tea from Tan Cuong in Thai Nguyen Province is one of only two in the country that has been awarded Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) by the Vietnamese government. The PGI classification is limited to a handful of communes around Tan Cuong and originally required the tea to be produced from the Trung Du cultivar. Tan Cuong tea, which is traditionally rolled into a small hook shape, is most commonly produced by small family businesses who both farm and process the leaf. Whether the Trung Du cultivar restriction will continue to apply is not completely clear as a program is underway to progressively replace the long-lived but low yielding Trung Du with more productive cultivars. Whether a change to cultivar is possible without altering the character and taste of the tea could well be a challenge.

The typical aroma and taste of Tan Cuong tea is of fresh-cut grass often complemented by young rice, toasted nuts, and brown sugar. There is some bitterness on the tongue but this is offset by a long sweet (often floral) aftertaste. It is a tea that may appeal to fans of the grassier Chinese and Japanese green teas and would be an easier transition than switching to Vietnamese wild green teas which offer many different characteristics.

A ‘buyer beware’ word of caution is that the PGI is not rigorously managed, making provenance difficult to prove. The probability of fake labeling is high and as one online friend commented, “I’ve never seen a Thai Nguyen tea advertised that didn’t claim to come from Tan Cuong”.

Oolong Teas

Central Highlands Vietnam tea growing regions

The boom in Vietnamese Oolong tea production started back in the 1990’s and has developed at a fast pace, often in partnership with Taiwanese businesses – to the point that it can resemble an offshore tea production operation. Taiwanese knowhow, technology, and plant cultivars are widely used and much of the output is exported to Taiwan, although purely domestic Vietnamese brands do exist. It is an open secret that once in Taiwan the tea is generally marketed as Taiwan tea (at an appropriate premium) causing a good deal of friction with local producers. I have seen reliable statistics for oolong tea production in Vietnam but, as the most profitable of the teas produced, it accounts for a healthy 20% of export revenue.

Cui Yu, Jin Xuan, Si Ji, and Qing Xin cultivars were all imported from Taiwan from which Jin Xuan and Cui Yu are now approved for wide-scale planting in Vietnam.

The main centres for oolong tea production are in Lam Dong Province (in the Central Highlands) and Son La and Lang Son Province in the Northwest and Northeast. Although Lam Dong is situated in the south of Vietnam it is the single most productive province by volume of tea produced. From a personal perspective, I have yet to come across any stand-out Lam Dong oolong. There is good quality to be found but nothing beyond that. Perhaps it is a factor of geography with the two-season tropical climate of the south less friendly to top quality tea production. Or perhaps it is simply a personal bias!

In the Northern provinces, Moc Chau in Son La Province produces some excellent oolong teas of various styles (e.g. green, red and bug-bitten oolongs). While I am less familiar with Lang Son oolong teas, it is an oversight that will be addressed later this year.

Wild Teas

NorthWest Vietnam tea growing regions

Vietnam is one of a few countries in the world that are the home to large swaths of wild tea trees. Although likely to be a relic of past cultivation, rather than truly wild, their spread is associated with the movement of nomadic ethnic minority groups as they migrated southwards. It was usual to let the trees grow to their natural state, as small trees, and these are not farmed bushes gone feral. In Vietnam, wild teas will often be found marketed as shan tuyet, translating literally to ‘snow mountain’; where snow refers to the white hairs found on the young leaves.

Wild trees and shan tuyet should be synonymous but that is not necessarily the case. For example, the other tea with PGI status tea in Vietnam is called Moc Chau Shan Tuyet. Oddly, I have never come across this tea but, according to the information available online, it is produced using a shan cultivar from a farm rather than from wild sources. To my mind, wild tea should mean old trees, grown in mixed biodynamic environments and without human intervention other than harvesting. It makes them more ‘natural’ than ‘organic’, albeit without any certification. I see it as an opportunity lost if no attempt was made to protect and regulate the shan tuyet label; perhaps it will happen in the future.

The interest in wild teas has grown considerably during the years I have been involved with Vietnamese tea. At one time only areas such as Suoi Giang and Ta Xua were known for consistently good quality wild tea but this has now extended to other locations in both the Northwest and Northeast. The main concentration of wild trees is clustered around the mountains ranges of Tay Con Linh (Ha Giang) and Hoang Lien Son (Lai Chau, Lao Cai, Yen Bai). Amazingly, there are wild tea areas, notably in Ha Giang and Lai Chau provinces, which have high potential but where development is hampered through deficiencies in infrastructure, transport, and communications.

Also notable over recent years is the increasing involvement of Chinese traders buying basic wild ‘yellow’ teas in significant quantities. What happens to these teas once they cross the border into China is anyone’s guess but the suspicion has been that they become mao cha and resurface in Puerh products. In many ways, it is good business for the local producers who receive a good price and regular demand. On the other hand, as with oolong teas that are sold on as Taiwanese, it does nothing to build the reputation and value of the Vietnamese tea brand.

Tea drying or withering in Vietnam

Leaves from wild trees are used to make green, black, white and dark teas even though it is almost always green that is consumed locally. Producing white and dark teas is a more recent, higher value innovation and very good (young rather than aged) examples can now be found from several sources. It is to be expected that more and more of these styles of tea develop in the near future as techniques and marketing improve. I have yet to discover a good quality oolong made from wild leaf tea although there are some factories producing them. We carried out our own experimental in collaboration with our farmer friend in Son La but initial results were disappointing.

Wild teas can prove to be an acquired taste for the new drinker – particularly for green and white teas. Typically they do not have the same initial intensity of aroma that is found with farmed teas. Whether this is due to the larger, thicker leaves or the inability to nuance flavour by the application of fertilisers it is difficult to say; whatever the reason, wild leaves take longer to reveal their secrets in the cup. A good wild tea is more prominent at the back of throat than on the tongue and will offer a depth and complexity that persists over multiple infusions. From experience, some tea drinkers can never really take to them, while others find it difficult to go back to farmed teas once familiar with wild ones.

There are many opinions as to the varieties of wild tea trees in Vietnam but the arguments remain confused and inconclusive for me. When I was first introduced to wild teas I happily accepted them as var. assamica but since then I have seen many other theories ranging from var. parvifolia (or cambodiensis), var. pubilimba, var. shan and even Camellia taliensis. It is the topic of great internet debate but with little consistency. Some observers are quite unshakeable in their belief that all Vietnam wild trees are of a specific single variety or that certain varieties cannot possibly exist. Personally, I think the jury will remain out for some time to come. Human geography and changing international borders (the China/ Vietnam border was not established until after the Sino-French War of 1884) make a Vietnam specific variety unlikely. Trees are unconcerned with national borders and some areas of wild trees are so remote that they have almost certainly never been fully surveyed. Perhaps future genetic testing will provide the answers.

As an interesting aside, we recently provided samples to a study being undertaking by a division of the USDA. Although their research is continuing, initial analysis has suggested that spatial separation over the years may well have led to a specific Vietnamese cluster. Perhaps this is the plant equivalent of cultural evolution.

Tea Breeding and Cultivars

Tea bud and leaves

One of the early tea industry initiatives was to establish a tea research centre in Phu Tho Province (1918). Today its successor, known as the Northern Mountainous Agriculture & Forestry Science Institute (NOMAFSI), continues to manage plant breeding stocks and the development of new cultivars for use by the country’s farmers. Whereas tea plants grown in Vietnam were originally sourced from local stock and those of neighbouring China, the country now boasts a veritable United Nations of tea cultivars including those which can trace ancestry back to Vietnam, China, Taiwan, Japan, India, Georgia and Sri Lanka, among others.

With the tea industry seeking to achieve continued growth, the current primary focus is on developing plants with higher yields and improved resistance to drought, disease, and pests. As a result, farmers have been encouraged and incentivised to replace existing low productivity stock with a range of approved and new higher yielding cultivars. Principally, these include:

PH1 (Camellia sinensis var assamica): imported from Assam, India - suitable for black tea.

TRI 777 (Camellia sinensis var pubilimba): imported from Sri Lanka – best for green tea.

Kim Tuyen (Jin Xuan cultivar): imported from Taiwan and used for oolong and green tea production.

Phuc Van Tien (hybrid): an imported Chinese cross between Fuding Dabaicha and Yunnan large leaf – both green and black tea.

LDP1 (hybrid): a NOMAFSI cross between PH1 and Fuding Dabaicha – mainly black tea.

LDP2 (hybrid): a higher yielding NOMAFSI cross between PH1 and Fuding Dabaicha – black tea.

Other significant cultivars currently grown in Vietnam are: Bat Tien (Ba Xian - “Eight Immortals” in China, but imported from Taiwan); Thuy Ngoc (Cui Yu - “Green Jade”), Tu Quy (Si Ji - “Four Seasons”) and Thanh Tam (Qing Xin - “Green Heart”) – oolong cultivars imported from Taiwan; and Trung Du - a much older variety (var. sinensis f. Macrophylla, the big leaf Yunnan sub-variety) obtained from the original Phu Tho centre and planted extensively, from seed, in Thai Nguyen Province.

The TRI 777 cultivar has an interesting backstory in that it can trace its origins to Son La Province in Vietnam. Seeds were sent to Sri Lanka in 1937 where it developed to become a nationally recognised cultivar before being imported back to Vietnam in 1977. The other interesting anomaly is that in Vietnam it is classified as var. pubilimba whereas, in Sri Lanka, it is has been variously described as either var. assamica or var. parvifolia. A case, perhaps, of tea plant taxonomy not being as black and white as we might expect!

NOMAFSI also preserves a stock of wild (or shan) tea but these are maintained at a higher altitude centre in Ha Giang rather than at Phu Tho. In addition to the cultivars mentioned above, NOMAFSI has also developed several shan based tea cultivars for wider industry deployment.

Ambitious Growth Targets

Tea roller in Vietnam

According to the 2014 FAO statistics, Vietnam produced 93,000 tonnes of black tea and 95,500 tonnes of green tea, of which 71,500 and 64,500 tonnes respectively were exported. They produced 240,000 tonnes in most recent 2016 statistics. That year, in a submission to the May 2016 FAO Intergovernmental Group on Tea: Medium Term Outlook, Vietnam has projected a modest increase in black tea production but very ambitious plans for green tea growth reaching an export target of 285,000 tonnes by 2024 – cementing its place as the second largest exporter of green tea in the world. With the proposed increases expected to come from greater productivity rather than an increase in the land available for tea production, it reinforces the focus on higher yielding cultivars.

Unfortunately, FAO statistics recognise only black and green tea and do not categorise other tea types separately. It is reasonable to assume that oolong tea is included with green tea and that it forms a significant component of Vietnam’s growth projections. With China also predicting a close to 10% annual increase in green tea production (between 2014 and 2024) it raises the question of where the demand will be coming from.

All of the major tea types are produced in Vietnam. Black, green and oolong tea are processed in volume from farmed tea, while black, green, white and dark teas are made in far smaller quantities from wild trees. A tea known locally as trà vàng (literally ‘yellow tea’) is also produced from wild tree leaves but the process employed is closer to sheng puerh than it is to the yellow tea produced in China.

Major export markets for Vietnamese black tea are Russia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Middle East. Several large multinationals are involved in black tea production. Green tea production remains dominated by the smallholder/farmer who either produce their own tea or sell fresh leaf to nearby factories. The main export destinations for Vietnamese green tea are China, Taiwan and other countries of south-east Asia.

Final Thoughts

Vietnam continues to focus on mass-market commodity products and this is, understandably, equally true of its tea industry as it is an important source of export revenues and employment.Improvements in yields and quality for commodity tea through the introduction of new cultivars have proven successful. In general, however, Vietnam tea continues to suffer from a below average reputation.

The high-quality tea market remains relatively small although there are encouraging signs that it is growing. Vietnam can boast ideal conditions for producing excellent tea leaf material but this is yet to be turned consistently into top quality end product. Greater immediate financial returns exist for mass produced teas, rather than for specialist teas which depend on reputation and acceptance. In this context, the passing off of Vietnamese tea as Chinese or Taiwanese becomes an attractive proposition.

It would be nice to think that Vietnam can develop teas with their own identity rather than attempting to produce low-cost, Chinese copied products such as Long Jing or Tie Guan Yin. It may well be a slow process but I am confident that the positive developments seen over recent years in increasing the awareness of high-quality Vietnamese tea can continue. I would urge anyone who might be at all curious to give them a try.